With an estimated 1.6 million people living with either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis in the United States, there is increasing need to research safe and effective ways to manage debilitating symptoms that–pardon the expression–hit patients right in the gut. Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis are considered the two main types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and they manifest differently in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Ulcerative colitis is a condition characterized by chronic inflammation of mainly the colon, or large intestine. Crohn’s disease, however, can affect any part of the GI tract – a hollow, muscular tube that runs from the mouth, where food enters the body, to the anus, where undigested food is expelled. Common symptoms of both forms of IBD include diarrhea, abdominal cramps, bowel urgency, and weight loss. While the primary approach to treat these diseases is currently with medications that suppress the immune system, a rising number of patients and physicians are leading the charge to research how food and diet might also play a vital role in IBD management.

With an estimated 1.6 million people living with either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis in the United States, there is increasing need to research safe and effective ways to manage debilitating symptoms that–pardon the expression–hit patients right in the gut. Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis are considered the two main types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and they manifest differently in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Ulcerative colitis is a condition characterized by chronic inflammation of mainly the colon, or large intestine. Crohn’s disease, however, can affect any part of the GI tract – a hollow, muscular tube that runs from the mouth, where food enters the body, to the anus, where undigested food is expelled. Common symptoms of both forms of IBD include diarrhea, abdominal cramps, bowel urgency, and weight loss. While the primary approach to treat these diseases is currently with medications that suppress the immune system, a rising number of patients and physicians are leading the charge to research how food and diet might also play a vital role in IBD management.

To Dr. James Lewis, associate director of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Program at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, it makes sense that patients are looking to nutritional therapy as an adjunctive treatment for IBD. Lewis refers to Irritable Bowel Disease as an “immune-mediated disease because our current thinking is that the inflammation in the intestines is due to an overly robust response of our immune system against the microbes that live in our gut,” he explained in a recent interview. “And that’s part of the theory behind using diet as a treatment, that what we eat could potentially impact those microbes or how those microbes interact with our immune system.”

Lewis is the lead investigator of DINE-CD, a new clinical research study being funded by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). It is the first, national randomized trail of two dietary interventions to treat Crohn’s disease. In 2016, the Foundation received a grant from PCORI to look at how two diets – a Mediterranean-style diet and the Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD) – might reduce the symptoms and inflammation caused by Crohn’s.

The Case for Dietary Intervention When Living With IBD

One reason diet is under consideration for treating this disease is because the current medications used to treat Crohn’s “suppress the immune system,” said Lewis. “So we take the part of our body that’s designed to fight infection, fight cancer, and things like that, and we give medications…to make the immune system not work as well, to bring these inflammatory diseases back under control.”

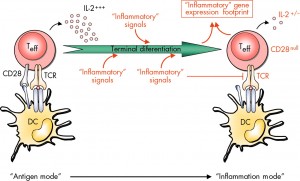

The medications that are most widely administered to treat IBD today are what are referred to as TNF Inhibitors. Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) is a cell-signaling protein, or cytokine, that is released by certain white blood cells in response to an inflammatory stimulus. This response is beneficial when your immune system is trying to fight a harmful bacteria, for example. But when a dysfunctional immune system erroneously attacks healthy cells, TNF may be produced in excess, leading to systemic inflammation, as found in conditions like IBD, rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. TNF inhibitors (like infliximab and adalimumab) target this protein to reduce an inflammatory response and stop disease progression. Unfortunately, by blocking this harmful immune response, other healthy immune responses might also be inhibited. This leaves patients susceptible to infections and other diseases, potentially increasing the risk of developing certain cancers.

The medications that are most widely administered to treat IBD today are what are referred to as TNF Inhibitors. Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) is a cell-signaling protein, or cytokine, that is released by certain white blood cells in response to an inflammatory stimulus. This response is beneficial when your immune system is trying to fight a harmful bacteria, for example. But when a dysfunctional immune system erroneously attacks healthy cells, TNF may be produced in excess, leading to systemic inflammation, as found in conditions like IBD, rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. TNF inhibitors (like infliximab and adalimumab) target this protein to reduce an inflammatory response and stop disease progression. Unfortunately, by blocking this harmful immune response, other healthy immune responses might also be inhibited. This leaves patients susceptible to infections and other diseases, potentially increasing the risk of developing certain cancers.

“It would be great to have a treatment strategy that was not so dependent on suppressing the immune system,” Lewis said. “And I like to believe that diet can be part of that strategy.”

He explained that some of the earliest evidence for the use of diet in treating IBD has involved studies when table food was taken out of people’s diets and replaced with meal replacement formulas. There has been considerable research on exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN), which involves solely administering a nutritionally-complete, liquid diet formulation for a defined period of time.

“And that has a fairly profound impact on the make up of the community of microbes that live in our intestines,” said Lewis. Modification of the microbiome has particularly been seen in children and adolescents with Crohn’s Disease.

“Unfortunately, we haven’t totally deciphered what the right changes are to be able to reproduce that [microbial] community structure, or the other factors that result in that working, while allowing people to consume regular table food,” he said. “And that is really one of our big interests–in trying to solve that.”

The DINE-CD trial is unique in that it will study and compare “two diets that you’d have rational reason to consume if you had Crohn’s disease,” he said in a June Q&A with Rebecca Kaplan of the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. The Mediterranean diet is familiar to many, with its emphasis on consuming fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds, with healthy fats coming from olive oil and fish high in omega-3 fatty acids – like anchovies, herring, wild salmon. bluefin and albacore tuna, sardines and freshwater trout. It is also characterized by a moderate intake of poultry, and a low consumption of red meat, dairy products, and processed foods. A 2017 review of meta-analyses of randomized trials and observation studies suggested a correlation between the Mediterranean diet and reduced risks of overall mortality, cardiovascular disease, overall cancer incidence, neurodegenerative diseases and diabetes. According to Lewis, it essentially follows the dietary guidelines that the USDA recommends.

“It’s associated with living longer, having less heart disease–which is a potential risk for people with Crohn’s disease–and is associated with lower cancer-related mortality,” he said.

The Specific Carbohydrate Diet is a grain-free diet that gastroenterologist Dr. Sidney V. Haas developed in the 1950s as a way to manage celiac disease. It was later re-popularized when biochemist Elaine Gottschall published Breaking the Vicious Cycle: Intestinal Health Through Diet With The Specific Carbohydrate Diet in 1987, after she found that following the diet improved her daughter’s case of IBD. The restrictive diet has a number of prohibited foods – including sugar, all grains, margarine, canned vegetables and fruits, and milk products high in lactose. “Mucilaginous polysaccharides,” or gelatinous plant substances containing polysaccharides and protein (like seaweed and aloe) are cited as being indigestible by those “who have compromised guts.” Aloe is also said to increase “the release of tumor necrosis factor, which is associated with IBD inflammation and increased immune stimulation,” according to Gottschall.

The Specific Carbohydrate Diet is a grain-free diet that gastroenterologist Dr. Sidney V. Haas developed in the 1950s as a way to manage celiac disease. It was later re-popularized when biochemist Elaine Gottschall published Breaking the Vicious Cycle: Intestinal Health Through Diet With The Specific Carbohydrate Diet in 1987, after she found that following the diet improved her daughter’s case of IBD. The restrictive diet has a number of prohibited foods – including sugar, all grains, margarine, canned vegetables and fruits, and milk products high in lactose. “Mucilaginous polysaccharides,” or gelatinous plant substances containing polysaccharides and protein (like seaweed and aloe) are cited as being indigestible by those “who have compromised guts.” Aloe is also said to increase “the release of tumor necrosis factor, which is associated with IBD inflammation and increased immune stimulation,” according to Gottschall.

Lewis said that while there is a plethora of anecdotal reports and uncontrolled research suggesting that SCD has a therapeutic effect, these studies have never provided a comparator group to the diet.

The Benefits of Diet Change on Crohn’s Disease Symptoms

Patient advocate Andrea Meyer, diagnosed with Crohn’s disease 18 years ago, is a person for whom diet change has proven beneficial. “I’ve had pretty much everything you can think of that’s a common symptom, across the board and at varying times over the years,” she said in a recent interview. “So I’ve dealt with diarrhea, rapid weight loss, even dealt with what they consider extra-intestinal symptoms, like skin irritation, eye inflammation.”

For her, making dietary changes was more challenging emotionally than physically. “We all have such emotional ties to food that to even be the one telling myself you probably shouldn’t be eating that, that was a harder hurdle than not physically putting in my mouth,” she said, with a laugh. “But once I started to see results, then it just got exponentially easier because I wanted more and more positive outcomes.”

Meyer said that the improvement of symptoms was gradual for her, though a decrease of general lethargy and increase of energy was experienced right away. “But intestinally, I think it took it a minute to sort of remain consistent,” she said. “That’s one of the things I’ve noticed about my disease, in general, is things can be on a delay. There are very few things that have an immediate, immediate impact. There’s a lot of things that kind of come as a result of time playing in.”

She found that she was better able to manage Crohn’s after she made the shift to a Mediterrean-style diet, just by “focusing primarily on organic fruits and vegetables, lean meat,” she said, “and cutting out the stuff that’s not good for anybody–so limiting sugar, limiting bad sources of fat and things like that.”

The DINE-CD Trial Seeks to Assess How Two Types of Diet Affect Crohn’s Disease

Both SCD and the Mediterranean-style diet followed in the trial are essentially “clean diets,” produced exclusively from fresh ingredients. Both also feature the exclusion of certain components of diet, such as processed foods. The DINE-CD study seeks to find out whether patients with mild to moderate of Crohn’s disease experience more improvement of their symptoms with one diet relative to the other. According to Lewis, it also seeks to find out whether elevated markers of inflammation in a subset of patients goes down more with one diet relative to the other.

“One of the hypotheses of how these various, whole food diets work is that they’re made from fresh ingredients, without additives, all organic food, etc. The other is that there’s certain components of the diet that you need to exclude,” Lewis told Foundation vlog listeners. “We don’t know whether you actually have to exclude those additional components, or [if[ it’s good enough to have your diet from pure, fresh ingredients, etc. So, at the end of the day, by comparing how people do between these two diets, [the study] should help us be able to answer that question.”

Lewis admits that the restrictive Specific Carbohydrate Diet is “much more of a challenge,” for patients to follow on their own. However, trial participants receive “all the food the they should need for the first six weeks of the study.” Once a week, seven prepared meals will be delivered for free to their homes. Dietitians are one of many resources made available to participants to help guide their food consumption during the latter half of the study.

DINE-CD is open to patients over the age of 18, with mild to moderate symptoms of Crohn’s disease. Patients are requested to keep whatever their medications they’re on at the time of enrollment at a stable dose throughout the study. The trial runs for 12 weeks, during which participants are required to visit one of 32 study sites for blood and stool testing at the beginning of the study, at six week and when it concludes at 12 weeks. Patients are also required to fill out a brief online questionnaire each day, which helps to track their symptoms. Lewis said the research study will be assessing whether patients have a resolution of their symptoms and of inflammation, the latter of which will be measured by blood tests.

DINE-CD is open to patients over the age of 18, with mild to moderate symptoms of Crohn’s disease. Patients are requested to keep whatever their medications they’re on at the time of enrollment at a stable dose throughout the study. The trial runs for 12 weeks, during which participants are required to visit one of 32 study sites for blood and stool testing at the beginning of the study, at six week and when it concludes at 12 weeks. Patients are also required to fill out a brief online questionnaire each day, which helps to track their symptoms. Lewis said the research study will be assessing whether patients have a resolution of their symptoms and of inflammation, the latter of which will be measured by blood tests.

This study is unique in that it was driven by tremendous patient interest, thanks to its partnership with IBD Partners, a patient-powered research network. The network offers patient members the chance to pose research questions most of interest to them, which is how the DINE-CD study arose.

“We looked through the questions proposed, and diet-related questions were at the top of the list,” Lewis explained in the Q&A with Kaplan. “And then we were lucky enough that the PCORI had an opportunity to apply for support for clinical trials that would answer questions that were important to patients.”

Kaplan, the Foundation’s public affairs and social media manager, urges anyone with inflammatory bowel disease to join IBD Partners. “It is a really easy way for you as a patient to have an impact on IBD research,” she said.

Researchers had “all the evidence in the world” that diet was important to patients, according to Lewis. ”When I see patients in the office, uniformly, I would say the number one questions that you get is ‘What should I be eating?’,” he said.

Why What You Eat Might Help Manage Crohn’s

While there are significant clues hinting at the important role that diet might play in managing IBD, the UPenn senior scholar of clinical epidemiology and biostatistics admitted that scientists remain unsure what really causes certain people to develop Crohn’s disease. “We know that your genetics contribute, but genetics contribute at most 30 to 40 percent. So there has to be some environmental exposure that is important here,” he told the Foundation. “Diet is one of many that could be playing a role, and it’s one that is easily modifiable. And so, there is the potential that with the appropriate dietary modification, one might be able to be on less immunosuppressant medication as opposed to more.”

Lewis said that a number of observational studies have shown that treating patients with a combination of anti-TNF medications and exclusive enteral-nutrition therapy might be more effective than just taking the medication alone. This suggests that “understanding what the right diet is could be a really important adjunctive therapy for patients with Crohn’s disease,” he said.

Diet is one of the few aspects of IBD that patients can control. Yet, with no conclusive research on the effect of table food diet on Crohn’s disease, up to this point, physicians have struggled with knowing what to tell their patients. “Participating in trials like DINE-CD will help us really get to a scientific answer,” Lewis said in our interview. “So hopefully, the next time that [patients] go to see their physician, and they ask, ‘what should I be eating?’, the answer won’t be, ‘I don’t know.’”

Click here to learn more about the DINE-CD study. If readers are interested in participating in the study, they can visit Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation to locate a site nearby. The 32 sites span from Massachusetts to California, with numerous locations in New York, Illinois and North Carolina.

Leave a Reply