With an extremely active mind and the constant distraction of chronic pain, for many years I felt that the practice of meditation was off-limits to me. Coming to so-called quiet standstill released a seemingly endless flow of thoughts upon thoughts. And when I wasn’t struggling to silence those, I was coaxing my defiant body to release tension and pain from tight and spasming muscles to slip into that state calmness. A time specifically set aside for stillness and peace become an active battle with both my body and my mind.

With an extremely active mind and the constant distraction of chronic pain, for many years I felt that the practice of meditation was off-limits to me. Coming to so-called quiet standstill released a seemingly endless flow of thoughts upon thoughts. And when I wasn’t struggling to silence those, I was coaxing my defiant body to release tension and pain from tight and spasming muscles to slip into that state calmness. A time specifically set aside for stillness and peace become an active battle with both my body and my mind.

“All the effort that most people put forth in trying to create a non-agitated state…is itself a form of agitation,” meditation teacher Dean Sluyter said in a recent interview. “Everything we thought was a distraction from the meditation is actually a meditation. Concentration on putting thoughts away is the distraction.”

Sluyter explores this unique view of meditation in his latest book, Natural Meditation: A Guide to Effortless Meditative Practice. Natural meditation for the rest of us is distinct from other approaches that rub against our true nature. Approaches that require strained concentration, adopting a “spiritual” attitude or copying someone else’s lifestyle are unnatural, Sluyter writes, which is why they require so much commitment to stick to. On the contrary, natural meditation is “as natural as breathing, walking, laughing, or being the I that you already are.”

Sluyter draws from decades of studying and teaching various forms of meditation. He first began studying meditation in San Francisco during the ‘60s. He said he started in Zen meditation, but he found it too restrictive. His teacher told him that Zen was not for everyone; in fact, it was not for most people.

He then became acquainted with Maharishi, who had developed the Transcendental Meditation technique. He said, “There was an element of effortless, but the only suitable vehicle for settling down in the effort of the effortless way is through this set of mantras.”

People who are drawn to meditation are often discouraged by the notion that it requires a lot of work, specific rituals or a certain teacher or technique to do it “right.” You might think meditation requires that you to sit like a stone, as Zen practitioners do. Or maybe you feel you have to utter specific mantras, as in Transcendental Meditation.

“But it’s not true. The door is everywhere,” Sluyter said. “All those things people think they need to do to meditate are counterproductive.”

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7YOJppqH_3c]

In natural meditation, there is no need to try to still the body and the mind. Sluyter argues that there is stillness that underlies body and the mind that is our natural state. “You don’t have to push away thoughts, which come and go,” he said. “Relaxation and tension come and go, but you remain as their silent witness.”

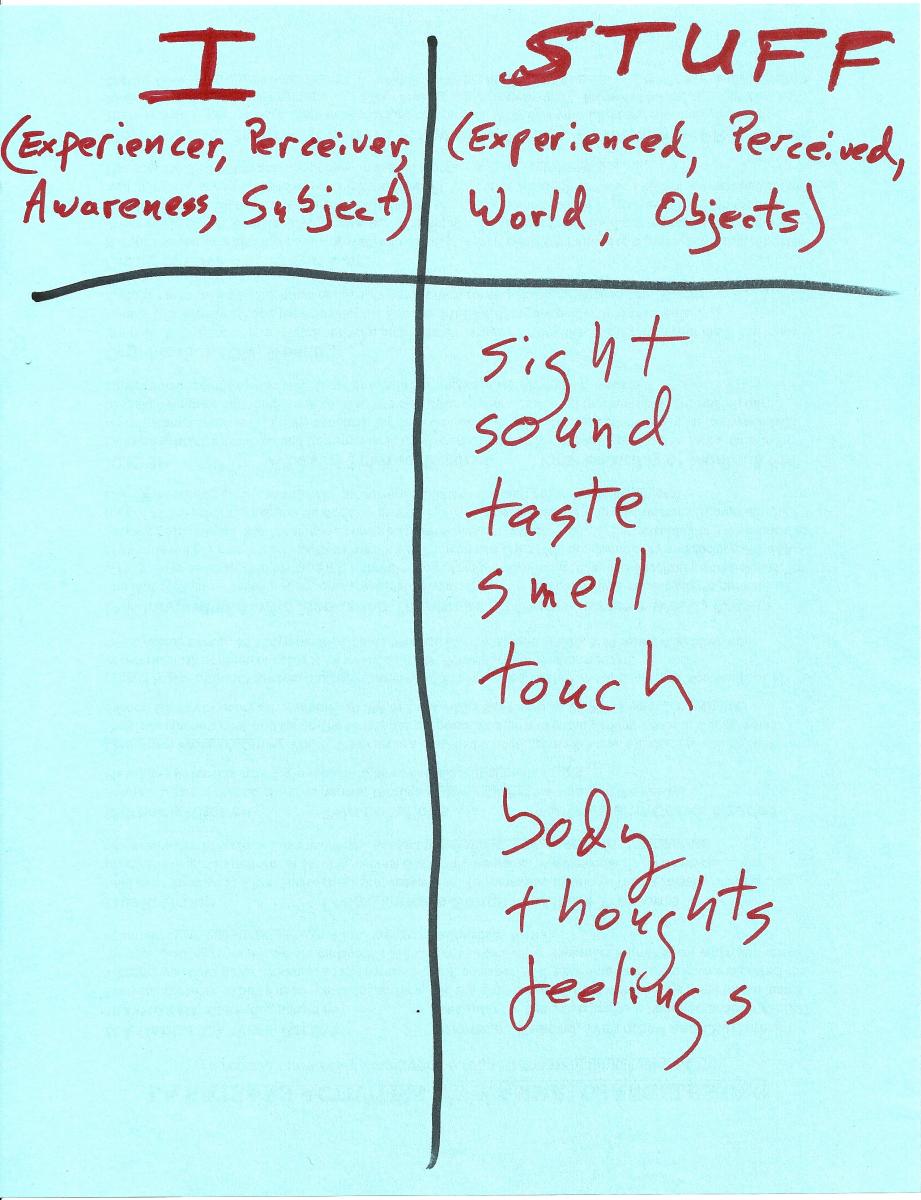

The first step toward embracing that underlying stillness that is our natural state is to recognize what Sluyter calls the I-sense. “No matter how much our experiences change, one thing always remains the same: the presence of an experiencing awareness, which we can call ‘I’,” he said.

This awareness is present at every moment of our lives, even as our thoughts and feelings constantly change. It is there no matter how old we are, even as our body ages. “It’s that inner ‘aaaah’ that doesn’t depend on our accomplishments, health or anything else. We don’t need to create or maintain it,” Sluyter said. “Just rest in the I-sense. Just bring your attention to this always-present experience of being aware.”

He urges you to imagine having just woken up from surgery or a coma in a completely dark and soundproof room. Numb and unable to move your body, lacking any input from the senses, you still are aware of your existence. The sense of presence, in between the periods of thought, is what he describes as I-sense.

“It’s the lighting up of conscious presence, which is there prior to any particular thinking or particular feeling,” Sluyter said. “There’s just is-ness, but we’re not generally aware of this pure being-ness. Meditation on the ‘I’ ignites for us being awake in that pure being-ness that is there every time.”

“It’s the lighting up of conscious presence, which is there prior to any particular thinking or particular feeling,” Sluyter said. “There’s just is-ness, but we’re not generally aware of this pure being-ness. Meditation on the ‘I’ ignites for us being awake in that pure being-ness that is there every time.”

The I-sense is not male or female, conservative or liberal, young or old, black or white. While we can observe different colors, sounds and thoughts, our awareness is beyond sight, sound and thought. “Ask yourself, is it possible that I am anything but formless, colorless, soundless awareness?” said Sluyter. “You are conscious presence.”

Once we have this awareness of conscious presence, Sluyter invites us to meditate on a single breath. “It’s not focusing on the breath,” he said. “Easily rest your attention on the process of the single breath.” As you slowly and deeply breathe in, pause and take note of where you feel it in the body—in your lungs, your diaphragm, your nostrils or even your skull? Exhale and then pause at the end of the out-breath.

“That’s simple. I love it because it’s just a single breath. You don’t have time to knot it up,” he said. Your role is simply to observe; you’re not trying to concentrate or clear the mind or feel a special way. Simply be with the breath. Once you feel settled down, enjoying the pleasantness in the exhalation, again meditate on a single breath.

“You’re never counting breaths. A single breath is all we ever have because it’s right now,” he said. “Do you ever wake up, and it’s tomorrow? No, it’s always today. It’s never 10 minutes from now or 10 minutes ago. Just keep noticing that it’s always right now. If you really pay attention to that, you realize that things aren’t going; they’re just here, now.”

Sluyter said that meditation is settling back into conscious awareness, realizing it’s there as the background of our experience all the time.

In his book, Sluyter answers common questions people have about meditation, such as when and where to practice, in what position, for how long. While he writes that one should meditate when he or she will actually do it and that one can “find your silent core anywhere,” he does offer suggestions for helpful ways to get into your practice, from sitting positions to types of breathing. He also presents different approaches to meditation, whether focusing on sensation, the heart center, sounds (natural sounds, found sounds or mantras), the vision of the open sky or on self and other, love, or vacancy—where we’re no longer clinging to the narratives that we use to define and confine our selves.

He also writes about the bounty of benefits one experiences after meditating over time. One can relish in the “essential delicious of beingness itself” and call up that feeling again and again throughout the day. Other effects of meditation include improved physiological and mental health, better focus, clearer thinking and being less reactive, as well as learning to stop fixating on self-defeating feelings and thoughts and to address emotions before they take deeper root in both the mind and body.

“You can practice every day. It’s good to dip into that flavor of boundlessness and effortlessness,” Sluyter said. While he feels its good to have a regular practice time daily, he also encourages finding meditative moments throughout the day, whether while revving for the red light to turn green or waiting in the doctor’s office for an appointment. By doing so, he said, “You will never again wait in your life.”

“You can practice every day. It’s good to dip into that flavor of boundlessness and effortlessness,” Sluyter said. While he feels its good to have a regular practice time daily, he also encourages finding meditative moments throughout the day, whether while revving for the red light to turn green or waiting in the doctor’s office for an appointment. By doing so, he said, “You will never again wait in your life.”

“The door is everywhere,” Sluyter repeated. He talked about the meditation class he began teaching at a prison in New Jersey in 2005. “These guys are masters of meditation because there’s so much they cannot control. The voice over the speaker rattles the bone. There’s nothing you can do about it.”

In a noisy, crowded restaurant, you manage to tune out the other conversations to speak to the people with whom you are dining. You can learn how to do the same with meditation, with both outside distractions and niggling thoughts.

In his book, Sluyter dispels the myth that we need to tame the monkey mind to successfully meditate. The monkey mind is this idea that our untrained, wild and practically primitive mind jumps incessantly and naughtily from thought to thought and must be tamed into submission—and stillness. Calling this one of the “single biggest, most damaging, most counterproductive” notions in the field of meditation, Sluyter instead believes that thoughts themselves are not a hindrance to inner peace and freedom.

Sluyter says the more you try to chase the monkey mind, the more power you give to thoughts. In the attempt to harness mental activity, you are exerting more mental activity. Asking the question, “How do I ignore thoughts,” is another thought that should simply just be ignored, like your co-workers’ convoluted and boring prattle, the distracting din of other conversations at a restaurant and the jarring commotion of a prison yard.

“The moment you realize you’ve been caught up [in thoughts], you’re not longer caught up, because you’ve realized it, so there’s nothing you have to do,” he writes.

Rather than engaging and being at the mercy of your thoughts, Sluyter writes that we can look at them for what they really are—fluctuations, like the waves of an ocean. When you can witness rather than immerse in your thoughts, you are no longer victim to them.

“We thought we’d find serenity by quieting our thoughts, but our thoughts quiet themselves as we sink into serenity—it’s a side effect,” he writes.

I shared with Sluyter my transformative moment with meditation when I realized I need not fight my body to be able to meditate either. After focusing on the breath and doing a body scan, I found that could direct my attention to different parts of my body that were tense or in pain and breathe into them instead, encouraging them to release and to let go.

I shared with Sluyter my transformative moment with meditation when I realized I need not fight my body to be able to meditate either. After focusing on the breath and doing a body scan, I found that could direct my attention to different parts of my body that were tense or in pain and breathe into them instead, encouraging them to release and to let go.

“This is what you’ve been handed. Chronic pain is the guru,” said Sluyter. “The thing that you can’t change that you think you have to change is your guru. That is your personal, orchestrated, made just for you door. The stumbling blocks are your path. Doesn’t mean become passive or apathetic. When you can’t change something, that’s the thing for you to learn from.”

Sluyter has learned to lead meditation while enduring tinnitus and through an eye condition called detached vitreous, which he developed a few years ago. “At times, my eyesight is like looking through cobwebs,” he said. At first he felt, “I am too picky to be okay with this. I’m someone who wonders, should this be a comma or semi-colon after reading through something I’ve written a dozen times. It became the guru for me. Let it be. Saying, ‘let it go,’ doesn’t mean the thing has to go away…I can go for days letting it be, not thinking about it; it’s just other conversations at other tables.”

Sluyter likens meditation to a turtle drawing its head and tail inside. “It’s like soaking in a hot tub, marinating in that is-ness, that silent beingness,” he said. “It’s a great tool for getting through life without life overwhelming you.”

Having had the fortune of spending time with many enlightened masters of meditation, Sluyter said, “They laugh a lot. They’re joyous in ways they can’t convey to other people, but they can show them how.”

You can learn more about how to practice natural meditation at www.NaturalMeditationBook.com. Purchase Natural Meditation: A Guide to Effortless Meditative Practice online at Amazon in paperback, e-book or audoibook. And I will be giving one lucky reader who comments on this post a free copy of the book.

Leave a Reply