I know I’m not alone in trying to process the terror and violence that recently erupted in Charlottesville, VA. The brutal altercation between rallying white supremacists and counter-protestors has slammed more tidal waves of horror, disbelief and sorrow about race relations against the rocky foundation of our country. It has compelled a period of deep reflection on what the United States of America was really founded upon and where the state of our nation truly is today. Fighting my own despondency, I’ve voraciously read and shared informative articles, insightful posts and soul-searching videos on Facebook, as well as uploaded inspiring images and uplifting quotes on Instagram. But beyond mediated expressions of hope, healing and (sometimes tough) love, though, I–a writer–have not been sharing many of my own words on what I think and feel.

I know I’m not alone in trying to process the terror and violence that recently erupted in Charlottesville, VA. The brutal altercation between rallying white supremacists and counter-protestors has slammed more tidal waves of horror, disbelief and sorrow about race relations against the rocky foundation of our country. It has compelled a period of deep reflection on what the United States of America was really founded upon and where the state of our nation truly is today. Fighting my own despondency, I’ve voraciously read and shared informative articles, insightful posts and soul-searching videos on Facebook, as well as uploaded inspiring images and uplifting quotes on Instagram. But beyond mediated expressions of hope, healing and (sometimes tough) love, though, I–a writer–have not been sharing many of my own words on what I think and feel.

Despite being a practitioner and teacher of radical self care and mindful meditation, I’ve been doing more reacting and responding to the collective than intentionally sitting still and alone long enough to get to a mental place where I can physically take action. As someone living with chronic pain and a neuromuscular movement disorder, I find that I greatly take on stress in my body, stirring “issues in my tissues.” Thus, in these intense and tumultuous times, it’s especially vital to make time for cleaning house mentally, with self-care practices like deep breathing, exercise, meditation and journaling. When I can ground myself and once again find my center, I am in a far better place to speak out, stand up and act in the name of release, recovery and revolution that’s long overdue.

Doing the Inner Work to Release Oppression’s Hold

So I took it to heart when social justice and liberation coach Andréa Ranae Johnson issued the challenge–or invitation, really–for coaches, healers, spiritual teachers and leaders to look within to uncover how oppression influences how we personally view ourselves and others. By doing so, Johnson said in a live Facebook feed, we will then truly be able to use our skills and social platforms to help dismantle “white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism, ableism and transphobia” to engender healing in our society. While many coaches, teachers and healers might shy away from addressing the subject of oppression with their students and clients, Johnson believes that not doing so does a disservice to those people we want to help.

“How can you be of service if you don’t know what they’re dealing with?” Johnson said. “How can you truly understand and serve them…without understanding what’s going on in their world, what’s impacting them, or how they’re impacting others?” We are invited to ponder what truly is the point of healing and growth work, if not to learn the perspective of those we serve and to help them uncover where they are stymied by frustration, pain, anger and loss.

As teachers and influencers in our communities, we may find ourselves wondering how can we positively affect change in the wake of physically violent and emotionally traumatic social unrest in our fractured society. Johnson said that in order to truly help others, we must first unpack our own beliefs and experiences with oppression. “Where are you holding racist beliefs or even experiencing racism…and how are you internalizing that? How is that affecting your wellbeing? How is that affecting your body? How is it affecting your mental state?” she said.

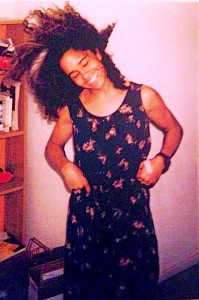

As a personal example of where she feels white supremacy resides in her, Ranae expressed her self-consciousness about how her ‘fro hairdo looks live on camera. “That’s a place where I need to unpack that,” Ranae said, with a laugh, “because my hair is beautiful. And it being in its natural state–me being worried about? There’s something there. There’s white supremacy there.”

I could instantly relate to her self-consciousness. As one of the few non-white children raised in my small, New England suburb, I grew up literally battling with my hair and my body to try to look more like the other (white) girls. By my teens, though, I felt more empowered by international travel and greater knowledge of the outside world to be proud and free to be me. I found myself rebelling against teachers who I felt were trying to pigeonhole me as their token spokesperson for black culture. I offered perspective to my track and field teammates who argued that they could never beat the girls from the city because they were black and, thus, genetically superior at running. And I had to stand up for myself to my first boyfriend’s family who suffered from European nationalism and generational racism. By the time I settled into a more culturally diverse university in California, I was ready to literally let my hair down.

I said goodbye to blow dryers and straightening perms, inviting my locks to unfurl big and curly. I chose my Jewish boyfriend and diverse circle of friends, instead of having them chosen for me by segregating campus organizations and communities. I was part of my college’s nascent program in comparative studies in race and ethnicity, earning an undergraduate research grant for a project exploring how ethnic and cultural identity is expressed through popular culture–a subject I would go onto to teach to high school students a decade later. I studied black music history and played jazz, while I also spinning circles in flow skirts at hippie concerts. I embraced the melting pot that is my personal ethnic background, where I had the freedom and felt safe to do so.

I said goodbye to blow dryers and straightening perms, inviting my locks to unfurl big and curly. I chose my Jewish boyfriend and diverse circle of friends, instead of having them chosen for me by segregating campus organizations and communities. I was part of my college’s nascent program in comparative studies in race and ethnicity, earning an undergraduate research grant for a project exploring how ethnic and cultural identity is expressed through popular culture–a subject I would go onto to teach to high school students a decade later. I studied black music history and played jazz, while I also spinning circles in flow skirts at hippie concerts. I embraced the melting pot that is my personal ethnic background, where I had the freedom and felt safe to do so.

Yet, when I moved back to the northeast, I once again felt the pressure to conform, at least a little. While I tried to claim re-sleeking my hair was for ease of styling, I know I was buying into the ideals of others around me. In a far less diverse community, I found myself once again accepting the myth that having big hair and a big personality was a negative thing and that using my voice boldly was unacceptable–which was more than hinted at by my dominant boyfriends and by my male doctors. Despite my petite physical frame, I was afraid to be perceived as a loud, bold, black female.

Is it ironic that one of my role models for voicing health concerns and needs over the years has been my tall, insistent-to-the-point-of-rude, Jewish female friend? Most of the specialists I’ve seen over the last nearly two decades of living with debilitating chronic illness have been white males who have diminished my pain and mansplained my symptoms, as if I couldn’t possibly know when something is seriously amiss with my own body. Growing up in a very ableist culture as a multi-sport athlete in a family that “played through the pain” and avoided doctors as much as possible, I fought years of excruciating pain, severe sleep deprivation, increasingly debilitating fatigue and the patriarchy, as male doctors hinted that I was a malingerer or that they thought my symptoms were all in my head. Taking ownership of my own healing journey, I finally found a female doctor who encouraged me to take my symptoms very seriously and to take the necessary medication to work up to being strong and stable enough for healing to begin to take place. I willfully rebuked the male doctors who either told me I would never get better or who, despite wonky bloodworm and debilitating symptoms, told me I looked great and was perfectly healthy.

Identifying Oppression in Order to Heal

Johnson said that “the things that we’re wanting to heal, the things we need to heal in our personal lives–whether it’s how we think about ourselves, our self esteem, or even if it’s our physical health or our spiritual health–it’s all related and it’s all connected to oppression in some way, in some form.”

Living with an ‘invisible illness,’ it is especially hard for others to take your conditions seriously if you don’t yourself. I couldn’t “tame my wild symptoms” until I learned how to manage them–or, at the least, not to needlessly exacerbate them with unhealthy food, high amounts of stress and the physical taxation from over-exerting myself to live as close to a “normal life” as I could. Pushing too hard when I’d reach a more manageable period of disease, I’d find myself rebounding with even more complications.

It has been a journey that’s seem much trial and error, and I’ve had to undertake a lot of physical and mental reconditioning. After growing up in a culture where my body was praised only for its physical strength, flexibility and thinness (something for which I was also oddly shamed), it was incredibly humbling to live for a decade with an illness mostly unobservable by the unstudied eye until–quite suddenly–my mobility was completely stripped from me. It was incredibly humbling to learn how to navigate the world in a wheelchair and scooter, to not be able to drive for three years and to have people treat me as fragile and helpless being when I fell. To add insult to the injury to my esteem, I helplessly watched my body balloon because of the only medication that helped to manage the symptoms. During this extended period in my life, I learned a lot about myself and the people I most wish to serve.

Serving and Teaching to the Individual

I’ve found that coaches, teachers and healers in my own life have either treated me too delicately when they observe my health challenges, or they push me too hard, too far, and too fast when they can’t see that there is more going on with my body than meets the eye. This is why, after becoming a sport yoga teacher, I’ve gone onto explore more accessible forms of yoga–learning to teach yoga to the individual (just as I’ve done with nutritional therapy and health coaching), taking into account one’s physiological and psycho-social challenges, and equipping myself with a full toolbox of pose modifications from which to teach. I am by no means perfect in the execution as I’m still in training, but I’m growing more aware of how to address different challenges my students might face, such as moving into poses with less mobile or bigger bodies. In my training for Yoga for All and in my role as an Accessible Yoga ambassador, I am also learning the power of language and how to create a culture of body positivity, consent, inclusivity and empowerment.

I’ve found that coaches, teachers and healers in my own life have either treated me too delicately when they observe my health challenges, or they push me too hard, too far, and too fast when they can’t see that there is more going on with my body than meets the eye. This is why, after becoming a sport yoga teacher, I’ve gone onto explore more accessible forms of yoga–learning to teach yoga to the individual (just as I’ve done with nutritional therapy and health coaching), taking into account one’s physiological and psycho-social challenges, and equipping myself with a full toolbox of pose modifications from which to teach. I am by no means perfect in the execution as I’m still in training, but I’m growing more aware of how to address different challenges my students might face, such as moving into poses with less mobile or bigger bodies. In my training for Yoga for All and in my role as an Accessible Yoga ambassador, I am also learning the power of language and how to create a culture of body positivity, consent, inclusivity and empowerment.

My early experiences as an academic teacher also made me keenly aware of the need to combat my own stereotypes and harmful beliefs to understand and hold space for the bias and oppression seen and experienced by my students. In my 20s, I taught reading at an inner-city school to primarily black and Hispanic children who were struggling to reach grade-level proficiency. I was one of the only teachers of color to whom my early elementary students were exposed. I took my example as positive role model quite seriously and was touched when students (mostly the girls) expressed a desire to become a teacher like me. Yet I was also forced to acknowledge my personal privilege as someone raised by parents who prioritized high achievement in academics and who grew up with in a mostly white, upper-middle class suburb with great, safe schools.

Coming from my background, I expected a lot from my students academically, and I erroneously believed that most had parental involvement and help with schoolwork at home, just as I did. One of the biggest reality checks came when a fervent learner suddenly become unruly in class and resistant to doing his work. Thinking he was being influenced by the more dominant and disruptive boys in the classroom, I was much later informed by his mother, who spoke broken English, that the boy’s father had been gunned down and killed earlier in the year. My privilege had led me to take for granted that: one, the boy had both parents at home to encourage him scholastically; two, that his mom was fluent enough in written English to be able to help him with his reading homework; and three, that there wasn’t deeper trauma–like gang violence–that triggered the boy’s emotional transformation.

As for the most resistant learner of the class, I was surprised to discover that he was raised by strict grandparents who greatly respected education. By having an open dialogue with them, we become allies; as they grew to know and respect me as someone sincerely invested in their grandson’s learning–rather than as yet another person biased against the boy to harshly discipline him–they encouraged him to respect me as well. They provided the encouragement and accountability at home that reinforced what I sought to teach him the classroom. I also realized that, as a student a couple years older than his classmates, he was bored with the familiar, “babyish” material. I had to recognize his considerable knowledge and experience by providing more complex work for him and extra praise when he rose to the challenge, just as my first grade teacher had done for me. Seemingly overnight, he began paying more attention, actively and positively participating in the class, and greatly improving his grades. With greater agency and empowerment, he was also happy to help tutor his fellow classmates. My experiences with all these children truly highlighted the importance of teaching to the student and making the effort to really learn about and understand their experiences and perspectives as individuals.

How Do Teachers Serve Others During Times of Uncertainty and Strife

When we are looking to serve others, Johnson reminds us that we have to “consistently be in the practice of asking and holding space for the question of, ‘where does [oppression] show up in my life’ and ‘where does it show up in [my students’/clients’] lives?’” It is my firm belief that when we have the opportunity, the platforms and the tools to do so, we healers/teachers/leaders must be willing and able to be an ally and advocate for our students and clients. For I can’t help but wonder what the civil rights activists of the 1950s and ‘60s–teachers and spiritual leaders like my grandfather and great uncle–would say about what we’ve done as a nation, and what we–I–have done as individuals, to honor their struggles for justice and equality. What are we doing to carry their legacy forward?

As leaders/teachers/healers, we are especially equipped with a powerful skillset and compassionate desire to help the people we serve to identify their pain points and areas of discomfort and trauma; to teach empathy, self-care and resilience; and to encourage agency and empowerment as they take the steps to physically, emotionally and spiritual heal themselves–individually and collectively, as members of community. By addressing their specific and unique needs, we provide reassurance that we too are a safe person for them to turn to and rely on for guidance and support; that even in this uncertain world, in the environments where we meet with them, together we can feel safe to take up space, speak out and stand up for what is good, what is just, and what is right.

[…] and individually–play in the perpetuation of fear and hate that leads to violent vengeance and stifling oppression we commit against one another. It’s the only way we will ever be able to acknowledge and heal our wounds and move […]